review originally published in farrago 2023 edition six

Otherworldly outtakes cut from the same cloth as World of Echo

The meditative primordial songcraft of Arthur Russell may very well be the highest calibre of earnest artistry. He was a key player in shaping New York’s downtown mutant disco scene (1981’s 24→24 Music), laid the foundation for ‘80s arty, sophisti-pop (2004’s Calling Out of Context), and even ventured into folk rock eliciting Bob Dylan comparisons (2019’s Iowa Dream). Many of these accomplishments, though, were cemented years after the fact. Russell’s sole mission statement under his name was 1986’s World of Echo, best described by the caption bearing this record’s sleeve: “crossing the line from vocal to instrumental and back”. In the next six years, his eccentric sonic exploration curtailed, due to his tragic and untimely passing from AIDS-related illnesses in 1992. Russell’s estate at Audika Records has meticulously unearthed his plethora of unmarked tapes, collating his work to keep his spirit alive for today’s generations. Consequently, Russell’s omnipresence in modern music is as ghostly as the man himself, with his music and history being posthumously pieced together.

The enigmatic Picture of Bunny Rabbit from 2023 comprises songs that didn’t make it onto World of Echo. In the latter collection, he quietly redefined minimalism in music, merely with spectral howls and his signature screeching cello. It is the culmination of his mind that was impossible to decipher. The electroacoustic and folk leanings are gorgeously tranquil, yet sparse as they are dense. It’s as if Russell dismantled every fibre of what constitutes a conventional song. Ambient and dub influences are present, but his soft voice ultimately plants his music in pop. Naturally, World of Echo is challenging, but eternally rewarding. It’s of the utmost avant-garde in musical works, however, this new compilation makes for an easier listen. Its brevity lends itself to greater accessibility, but surprises lie within—entrances to a world parallel to ours.

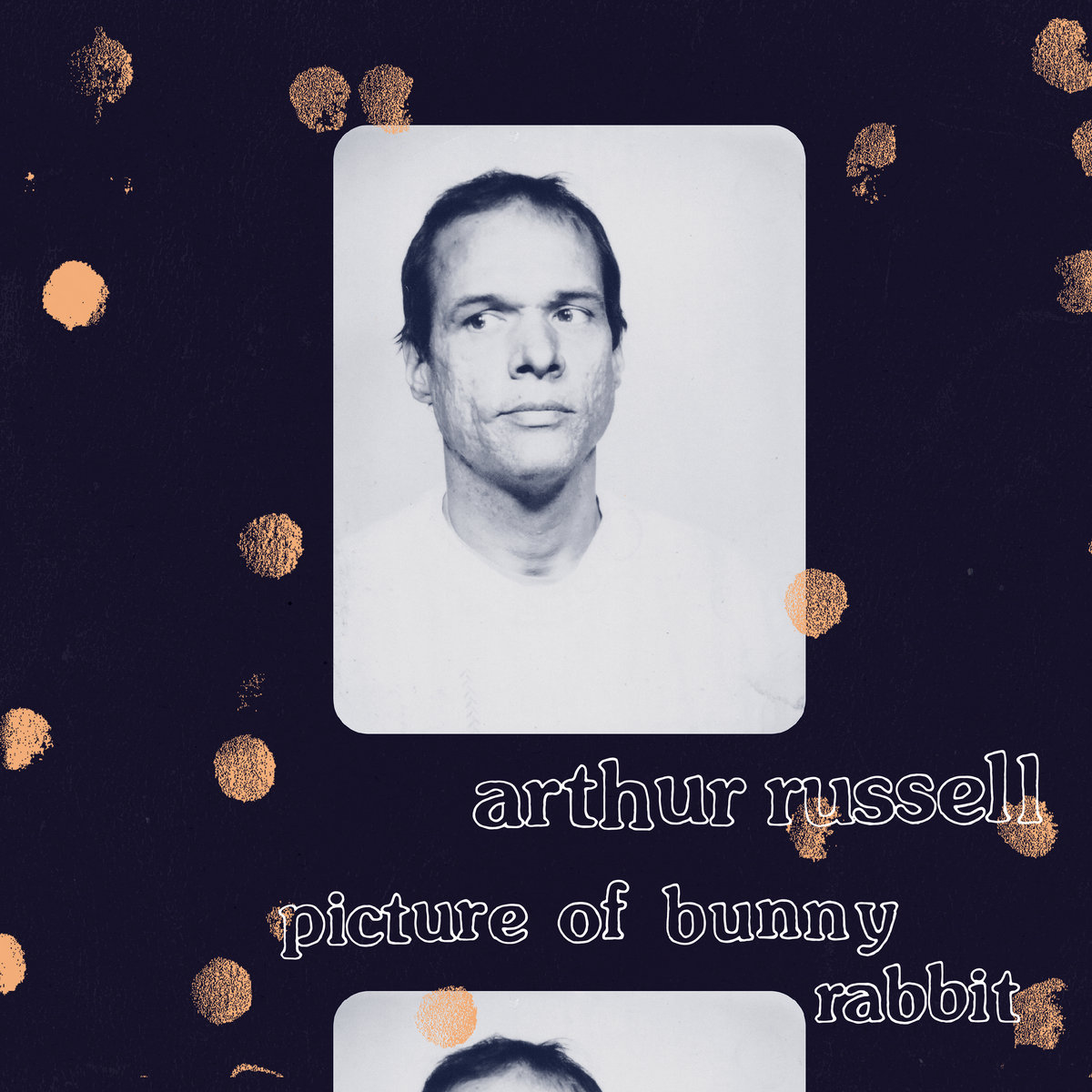

To reiterate, much like Russell, Picture of Bunny Rabbit is phantasmal. The way his photograph catches him precariously paints him as a rabbit-like apparition, swiftly escaping our grasp but still moving around. Listening to the songs is the same as conversing with him, where he delivers his psyche as brooding laments. ‘Not Checking Up’ is especially nocturnal, featuring his woeful mumbles about juggling external commitments: ‘It’s the only day / I’m off work / It’s the only time / I have at all’. ‘In the Light of a Miracle’ is like a prehistoric dance chant, with his dissonant cello guiding the way. Warbling synthesisers permeate the sparsity, akin to gentle ripples in a small pool of water. Russell’s repeating of his exclamations like a wisp—‘Holding in the light / Walking in the light’—infers a sense of hope in his oft-ominous poetry. Reaching the light, albeit in glimpses, is possible in the series of ‘Fuzzbuster’ instrumentals. ‘#10’ opens the collection with keyboards sounding pleasant bells, greeting the listener to the conversely suffocative musical emptiness. ‘#09’ is propulsive and beguiling, soundtracking moonless high deserts. Meanwhile, wistful ‘#06’ is the most impressive, evoking the same innocent self-restraint of indie bands Young Marble Giants and early the xx, marvellously foreshadowing the latter’s nightly indie pop of today. Russell’s twinkling acoustic guitar, harmonising with the funereal cello, is a sublime remedy for the disconcerting soundscapes in-between.

The album’s true centrepiece, uncharacteristically lurid, is the titular track, ‘Picture of Bunny Rabbit’. Russell was no stranger to long-form improvisation, but the allure of this voyage is implausibly isolated from his usual forte. No recorded music up to that point (1985–86) sounded like it. To me, it conjures a spellbinding pilgrimage into lucid imagination. Abrasive arpeggios bloat with distortion and glitch, as though trying to make sense of the surroundings. Bitcrushed cellos fleetingly hop around, as liberated as a jovial bunny. They don the uncanny strangeness of a grovelling anthropomorphic rabbit in a dapper suit. Familiar images, thoughts, and memories become crystallised, skittering as the disseverance from the physical plane continues. Russell’s bellowed cello shrieks like discordant church bells, leaving gashes on the eardrums. An incessant strangle by the incoherence. The gloaming is blood red like the eyes of a white rabbit, and only the listener in that moment is facing the discordance of inner scrutiny. Is this still the same Russell who dreamily mopes with his off-kilter baritone? By the conclusive stretch, when fully separated from oneness, it seems impossible. His only remnant is his cello, which cascades further into malevolence, until the haunting ringing abruptly peters out. Back at present. For those eight minutes, the listener is the only recipient of this labyrinthine, effusive ceremony. It is by far Russell’s most visceral piece bestowed upon ears, which otherwise would’ve been concealed eternally if not for his estate—stunning and beautifully chilling.

Russell’s thorough musical deconstruction was merely one facet of many. His curious art pop predates that of Peter Gabriel’s heyday, and even had a collaboration with the Talking Heads under his belt. When he wasn’t caressing his cello to sound a buoyant heart like skipping over water, Russell was at his most esoteric. The peachy flickers on Picture of Bunny Rabbit’s artwork are the luminous beams of inspiration that only Russell could see. He seized them, surpassing his creative peers—tragically too much so—but his ghostly portrait eyeing them is a trophy. We’re blessed with his spiritual guidance, tending to his artistry as loyal as a rabbit, and making sense of his vulnerability for ourselves.